Restoring What Law Erased: Leadership at the Intersection of Culture and Law

Restoring What Law Erased: Leadership at the Intersection of Culture and Law

Synopsis

The law, in its majesty, holds the power not only to emancipate but to efface, to offer protection with one hand while scripting erasure with the other. This Case Study shall traces one such paradox: how a statute - the Madras Devadasi (Prevention of Dedication) Act, 1947, framed during colonial rule and retained in post-independence India in the name of reform, came to criminalise a community, collapse a multifaceted identity, and displace a centuries-old art form from its original custodians. This is the story of Sadir, the dance of the Devadasis (erstwhile form of Bharatanatyam), and the Devadasis, a quasi-matrilineal community of South India.

Sadir[1], represents a felicitous union between the divine and the ever-auspicious brides of the divine – a celestial embrace of the mortal and the spiritual. It is a liberating portrayal of pure affection, wherein, the Devadasis expressed their unwavering devotion for Hindu Gods through agile footwork, graceful hand gestures, and radiant expressions. This depiction of devotion often bore undertones of eroticism. With the arrow of time, Sadir and the identity of Devadasis have undergone a significant evolution, with their trajectory being shaped by law, both customary and statutory. Among such laws, the Madras Devadasi (Prevention of Dedication) Act, 1947 stands out as particularly consequential. By collapsing the rich and multifaceted identity of the Devadasis of Madras into a reductive narrative of prostitution, the Act erased their artistic and cultural agency. In contemporary India, Devadasis – once revered custodians of a sacred art form, are now often equated with sex workers, stripped of representation and social dignity. The cultural history of the Devadasi tradition, alongside the legal trajectory of the 1947 Act, reveals that law, depending on its intent and application, can either suppress or sustain artistic expression. It is therefore imminent to reimagine legal reforms as frameworks that safeguard artistic heritage and the rights of its practitioners, especially in contexts as historically layered and socially fraught as that of the Devadasis. Aligning with this goal, through this case study, I seek to articulate the essence of my life’s work - mapping the legal and historic contours of art and its expression, shaping policy and jurisprudence to safeguard and collectivise artistic communities, and preserving the cultural rhythms that reside at the heart of our shared heritage.

What’s going on?

The Devadasi identity, weaves together the histories of bardic dancers, courtesans, and ritualists of India. In the literary expanse of the Sangam period (period between 300 BCE to 300 CE in the ancient South Indian history), and thereafter, during the Pandya-Pallava reign[2], and the subsequent ascendency of the Chola empire, Devadasis were portrayed as erudite dancers, gracing the courts, temples, and palaces, enjoying inordinate social visibility[3]. The rise of Vijayanagara empire in the Deccan during the 1300s formalised the customary practise of temple dedication, through which young girls and women were ceremonially offered to the God through ‘Pottukattuthal[4]’ – a symbolic marriage with the deity. Upon ceremonial dedication, they became Devadasis, the brides of God, and performed Sadir as part of their sacred duties within Hindu temples. However, since the 18th century, under the Maratha dominion and colonial rule, ‘Pottukattuthal’ tethered Devadasis to sexual economy and concubinage, rather than to sacrilege[5]. By 1858, with the British Crown assuming absolute control over South India[6], Devadasis were relegated to a ‘nautch’ identity – stigmatized as ‘fallen’ women of ill repute and questionable morality[7]. Likely, in the English imagination, Sadir was misrepresented as a ‘seductive art’ performed by Indian courtesans, accompanied by ‘amorous’ songs[8]. These moral inquisitions of the British government led to the emergence of the anti-nautch movement in colonial India. The anti-nautch movement, which opposed the Devadasis system and Pottukattuthal, culminated in the enactment of Madras Devadasi (Prevention of Dedication) Act, 1947. This legislation unjustly established a legal presumption that the six specified Devadasi communities, enlisted under Section 3 of the Act, engaged in dance or music performances inherently bear the identity of a prostitute. Additionally, Section 4(2) criminalizes the performance of the Devadasis’ dance by prescribing punitive sanctions. Notably, the exclusive scope of the Act of 1947 singularly targeted the custodians of Sadir – Devadasis and similar communities – while omitting others. This omission resulted in the appropriation of performance spaces previously occupied by Devadasi women by dominant castes. Likely, during a period when the performance of Sadir by Devadasis was criminalized under the law, individuals and communities outside the Devadasi tradition were afforded the liberty to claim the dance form, its repertoire, and its institutionalization as their own as ‘Bharatanatyam.’

Additionally, the 1956 Amendment to the Act of 1947, in alignment with Section 372 and 373 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860[9]– provisions that penalises prostitution – criminalised performances by Devadasi women under the penal law of India, thereby institutionalising the criminalisation of their art, identity, and way of life. Arguably, this legislation, along with its subsequent amendments and revisions by the post-independence State Governments of Tamil Nadu[10], Karnataka[11], Andhra Pradesh[12], and Maharashtra[13], created an environment conducive to the appropriation of Sadir by dominant communities, stripping the art from its original custodians.

From glory to misery, the worth of Devadasi identity in colonial and post-independence India was single-handedly shaped by law. This trajectory of evolution of the Devadasi identity and Sadir underscores the enduring impact of laws on cultural identity. The Madras Devadasi (Prevention of Dedication) Act, 1947, as this case study demonstrates, exemplifies the law’s dual potential: to serve as a tool of social reform while simultaneously becoming a conduit for cultural obliteration. Enacted under the guise of protection, the legislation overlooked the complexities of lived experience, collapsing a layered performative identity into a singular moral archetype and facilitating the legitimised appropriation of an art form through the very language of justice. This narrative illustrates the often-overlooked plurality of the implications and ramifications of law, how the same law that promises liberation may also instantiate exclusion. The Devadasi question thus becomes emblematic of a deeper juridical paradox: one that reveals the dissonance between legislative intent and lived consequence.

What action is being taken?

This issue unfolded predominantly in South India, especially in the Madras Presidency (modern Tamil Nadu), Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Maharashtra. These regions once preserved thriving Devadasi traditions, particularly in temples of Chidambaram, Tanjore, and Madurai. Under colonial governance and subsequent State legislations in post-colonial India, the socio-political climate shifted towards homogenised morality and Brahmanical cultural ideals, enabling upper-caste and elite appropriation of temple arts. Economically, the cessation of temple grants and royal patronage displaced many Devadasi families from their traditional livelihoods, forcing them to the peripheries of both urban and rural economies. Socially, they have been unjustly equated with sex workers or prostitutes, denied dignity, and deprived of fundamental rights and representation. Culturally, their art is now performed, commercialised, and celebrated by individuals who often fail to acknowledge the Devadasis’ foundational role in shaping and preserving the tradition.

While such discrimination continues to persist, it would be inaccurate to assert that the enactment of the 1947 Act was entirely unjustified or devoid of merit. Pottukattuthal, the ceremonial dedication of girls as Devadasis, undoubtedly called for reform, as by the 18th century, it had become entangled with the sexual economy surrounding temples. In seeking to abolish this practice, colonial administrators, missionaries, and Indian reformers believed they were dismantling exploitation. Yet, the Madras Devadasi (Prevention of Dedication) Act, 1947, while ending temple dedications, erased an entire community’s artistic, ritualistic, and cultural legacy by conflating all Devadasis with prostitution. This case reveals how laws, if imprecisely crafted, can perpetuate the very harm they aim to eliminate. If the State, in reforming, ends up silencing, does it not bear the responsibility to restore what it erased? And to what extent should the State have the authority to regulate cultural memory and artistic expression?

The lingering impact of the Act of 1947 continues to reverberate across the streets of India, even 78 years after its enactment, where Devadasi identity prevents a woman from enjoying succession rights [as evidenced in Saraswathi Ammal vs Jagadambal & Anr 1953 SCR 939][14], marital benefits [as evidenced in Dalavai Nagarajamma vs State Bank of India, Cuttapah & Ors AIR 1962 AP 260 and Kumari Baghyavathi vs Smt. Lakshmikanthammal AIR 1993 MAD 346][15], and dignity [as evidenced in Smt. Durgamma & Anr v. Shivashankara & Ors MFA No.8418 of 2007][16]. And, the appropriated iteration of their art – Bharatanatyam, which was elevated to the status of ‘classical’ by the State, remains inaccessible to the Devadasis in contemporary India. Despite the stated objectives of reform in the Act of 1947, the Government of India and respective State authorities have consistently failed to implement adequate rehabilitation mechanisms for women displaced as a consequence of the Madras Devadasi (Prevention of Dedication) Act, 1947. Simultaneously, the judiciary has demonstrated a limited interpretative vision, persistently viewing Devadasis through the legally imposed identity of ‘prostitutes’ rather than acknowledging their complex socio-cultural roles as artists, ritualists, and knowledge bearers. This failure has contributed to their political invisibility, cultural marginalisation, and economic exclusion. Although various policy think tanks have undertaken periodic studies on the condition of Devadasi communities, these efforts have largely lacked historical nuance and contextual understanding. Specifically, they fail to account for the Devadasis’ significant cultural relevance prior to their identity being conflated with prostitution. The absence of this historical consciousness has led to an incomplete and, at times, misguided policy response.

In addition to such efforts, notably, prominent performers of Devadasi lineage, such as T. Balasaraswati, sought to reclaim and recharacterise Sadir, the predecessor to Bharatanatyam, as an art form cultivated and refined by Devadasi women. Yet these interventions were largely overshadowed by the rising popularity of Bharatanatyam as a ‘classical’ form, predominantly shaped by non-Devadasi narratives and institutions.

In light of these systemic oversights, the following policy imperatives merit urgent attention:

- Rehabilitation and Protection:

The State must implement targeted rehabilitation programmes for Devadasi women who remain marginalised, many of whom, in regions like Ballari and Vijayanagara, continue to be subjected to covert temple dedications and are denied access to alternative livelihoods. Branded as prostitutes and stripped of artistic agency, they are forced into sex work with no recognition of their cultural expertise or legal rights to practise their ancestral art.

- Recognition of Cultural Custodianship:

The State must formally acknowledge the Devadasis as the original custodians of Sadir and, by extension, Bharatanatyam. While the contributions of all artists to the evolution of Bharatanatyam are valid, historical justice demands that the foundational role of Devadasis be equally recognised and taught as part of the dance form’s cultural narrative. The recharacterisation of the art form’s emergent history should be formally integrated into the curricula of art institutions and academies where performative dance traditions are taught within structured educational frameworks.

- Policy Reform and Reparative Frameworks:

The 1947 Act must serve as a precedent to examine other legislative interventions that have disrupted traditional artistic communities. Similar policies affecting the tawaifs and courtesans who shaped Kathak, for instance, require re-evaluation, reparation, and restorative cultural recognition.

- Intellectual Property and Cultural Protection:

There is an urgent need to include Traditional Cultural Expressions (TCEs) within the framework of India’s Intellectual Property regime. Such legal recognition would help protect the performative, ritual, and oral traditions of marginalised artistic communities from appropriation and erasure.

I have been working toward these goals by extensively documenting the often-overlooked history of the Devadasis, and other similarly placed artistic or bardic communities, seeking to accord them rightful recognition for their artistic and cultural contributions. In parallel, I have been actively engaged in advocating for policy reform within India’s Intellectual Property Rights regime, specifically, for the protection of Traditional Cultural Expressions and the legal recognition of custodianship over traditional art forms. As part of this effort, I have represented bardic communities during the past year of my legal practice, further reinforcing my commitment to cultural justice through legal advocacy. My engagement with the history of the Devadasis has profoundly shaped my commitment to writing about art histories that are frequently relegated to footnotes, yet are foundational to India’s cultural heritage.

Where do I fit?

The Afterlives of Law: A Personal Reckoning with Justice, Art, and Memory

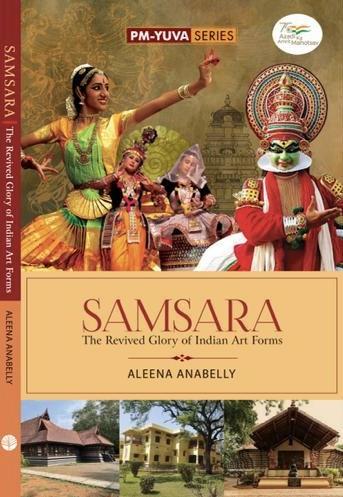

Over the past few years, my journey as a legal practitioner and scholar has been guided by a deep commitment to exploring how legal frameworks can protect the intangible: the stories, songs, and movements that live within traditional performative art forms. Much of my work has revolved around studying how legal systems, both colonial and post-colonial, have contributed to the erasure of cultural identities and the marginalization of artists. My writing has become my voice in this movement. Samsara: The Revived Glory of Indian Art Forms, my first book, published by the National Book Trust of India under the Prime Minister’s YUVA Mentorship Program, is the wellspring of this advocacy. It traces the arc of artistic revivalism during colonial rule and reflects on how law has historically shaped, and often suppressed, the lives of artists in India. A section of the book traces the emergent history of Bharatanatyam by recharacterizing the Devadasis as its original custodians, marking my first attempt at writing history through the act of redirecting credit to those people and places that have been forgotten or seldom acknowledged in contemporary discourse. The book’s reception reaffirmed my belief in the power of storytelling to drive reform. It was featured in the National Book Trust’s collection at the Seoul International Book Fair, 2023, and the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair, 2023. It was also included in the curriculum of the Rajasthan Higher Education Board, marking a small but significant step toward rewriting how young minds engage with law, culture and forgotten identities.

Samsara

My professional practice has deepened this journey. As a lawyer before the High Court of Kerala, I have had the honour of representing bardic communities and indigenous groups in intellectual property rights litigation, fighting for recognition of their collective artistic ownership. This experience has only solidified my belief that law, when wielded consciously, can help restore dignity and visibility to historically silenced performative traditions.

At the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India

Additionally, in recognition of my work at the intersection of law and art, I was invited to the Kala Sahitya Rachna Shivir, for an exclusive interaction with the Honourable President of India, Smt. Droupadi Murmu.

Pictures from Kala Sahitya Rachna Shivir at the Rashtrapati Bhavan, New Delhi, Indian, February, 2024.

From my experience, I have realised, my activism finds its rhythm in writing, in igniting conversations on the histories we inherit, the injustices we overlook, and the role of law in shaping both, particularly from the vantage point of cultural and artistic revival. Through every page I write, I attempt to preserve what was nearly lost and to advocate for a legal imagination that honours India’s diverse artistic legacy. Additionally, as a lawyer and writer, I have been advocating for the recognition of Traditional Cultural Expressions within India’s IPR regime. My legal work has focused on representing bardic and indigenous communities, and my writing seeks to restore erased histories. Yet, I face institutional resistance, academic gatekeeping, and a lack of funding for legal reform in the cultural space.

Leadership Insights

- Leading in this space demands more than knowledge, it requires persistence in the face of institutional indifference.

- Advocacy for marginalised cultures often invites resistance, especially from dominant narratives that feel threatened by reclamation.

- Effective leadership here means building coalitions with cultural practitioners, not just legal scholars.

- I have learned that humility and listening are more powerful tools than academic argumentation in many of these spaces.

Questions for My Peers

- How have you succeeded in making institutions receptive to forgotten or erased histories?

- Have you used storytelling to bring change in cultural narratives?

- What are some peer mentorship strategies you’ve used to support others in fields that intersect with heritage and justice?

[1] Sadir Attam or Dasiattam is the dance of the Devadasis; the erstwhile form of Bharatanatyam.

[2] Māṇikkavācakar (2002) The Tiruvāçagam, or, sacred utterances’ of the Tamil poet, Saint and Sage Māṇikka-Vāçagar G. U. Pope. Translated by G.U. Pope. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services.

[3] Tolkāppiyar (2001) Tolkāppiyam in English: Translation, with the Tamil Text, Transliteration in the Roman Script, Introduction, Glossary, and Illustrations Vellayagounder Murugan and G. John Samuel. Translated by V. Murugan and G.J. Samuel. Institute of Asian Studies; Murali , S. (1998) ‘Environmental Aesthetics Interpretation of Nature in “Akam” and “Puram” Poetry’, Indian Literature, 42(3), pp. 155–162; Vatsyayana, M. (2003) Kamasutra Wendy Doniger and Sudhir Kakar. Translated by W. Doniger and S. Kakar. Oxford University Press; Adigal, I. (1939) The Silappadikaram V. Ramachandra Dikshitar. Translated by V.R.R. Dikshitar. London: Oxford University Press “From that distinguished line of celestial nymphs, was descended Madavi, noted for her deeds of great distinction, as well as her broad shoulders and beautiful tresses which scattered the pollen of flowers. In dance and song, and in grace of form, she underwent training for seven years, succeeding in all three: and at the age of twelve, she was in position to display her talents before the reigning king who wore heroic anklets.”

[4] Nair , P.M. and Sen , S. (2005) Trafficking in Women and Children in India. Orient Longman. “As the story goes, it began with potttukattuthal, a version of the devadasi system, in which the girl is “dedicated” to god, and thereafter becomes the chattel of the “godmen” and their hangers-on;” Venkatraman, V. (2018) ‘Immoral traffic prostitution: Indian press on the abolition of Devadasi system in the madras presidency, 1927-1949’, SSRN Electronic Journal [Preprint]. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3152876. “The priest would tie the tali around her neck on behalf of the God. This ceremony was called as pottukattuthal. Symbolically she was bonded in marriage with a God and it was her chief duty to dance and sing before him to please him;” Srinivasan, A. (1985) ‘Reform and Revival: The Devadasi and Her Dance’, Economic and Political Weekly, 20(44), pp. 1869–1876. doi:https://www.jstor.org/stable/4375001.

[5] Kannabiran, K. (1995) Judiciary, Social Reform and Debate on “Religious Prostitution” in Colonial India, Economic and Political Weekly, 30(43), pp. WS59–WS69. doi: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4403368 “The agendas of reform, the non-brahmin movement, the colonial judiciary, and first wave feminism intersected to produce a hegemonic ideal of monogamous conjugality that would replace and recast the extended sexuality of the pre-colonial family in South India. The pro-abolitionists 'defined' the system largely in terms of the evangelical, bourgeois feminist and emerging nationalist frameworks of a new moral order - an order whose patriarchal constraints were very different from and alien to the patriarchal constraints that up to that point defined the choices available to female temple servants - and then attempted to find the system they were describing and its participants.”

[6] Hibbert, C. (2002) Queen victoria: A Personal History. New York, NY: Basic Books; Dirks, N. B. (2006) The Scandal of Empire: India and the Creation of Imperial Britain. Harvard University Press.

[7] Soneji, D. (2012) Unfinished gestures: Devadāsīs, memory, and modernity in South India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; Natarajan, S. (1997) ‘Another Stage in the Life of the Nation: Sadir, Bharatanatyam, Feminist Theory’, University of Hyderabad [Preprint]; Reddi, M. (1930) My Experience as a Legislator. Madras: Current Thought Press. “3. That countenance and encouragement are given to them (nautch girls), and even a recognised status in society secured to them, by the practice which prevails among Hindus, to a very undesirable extent, of inviting them to take part in marriage and other festivities, and even to entertainments given in honor of guests who are not Hindus. 4. That this practise not only lowers the moral tone of the society, but also tends to destroy that family life on which national soundness depends, and to bring upon individual ruin in property and character alike [Excerpt from the Memorial submitted Viceroy and Governor general of India, and Governor of Madras].”

[8] Fuller, M.B. (1900) The Wrongs of Indian Womanhood. Fleiming H Revell Company. “The nautch-girl often begins her career of training under teachers as early as five years of age. She is taught to read, dance and sing, and instructed in every seductive art. Her songs are usually amorous; and while she is yet a mere girl, before she can realise fully the moral bearings of her choice of life, she makes her debut as a nautch girl in the community by the observation of a shocking custom which is in itself enough to condemn the whole system;”

[9] Indian Penal Code (1860) S. 372 & 373

[10] Tamil Nadu Devadasi (Prevention of Dedication) Act (1947).

[11] Karnataka Devadasi (Prohibition of Dedication) Act (1982).

[12] Andhra Pradesh Devadasi (Prohibition of Dedication) Act (1988).

[13] Maharashtra Devadasi System (Abolition) Act (2005).

[14] Saraswathi Ammal vs Jagadambal & Anr 1953 SCR 939, (1953). “It is inconceivable that when the sages laid down the principle of preference concerning unmarried daughters they would have intended to include a prostitute within the ambit of that text.”

[15] Dalavai Nagarajamma vs State Bank Of India, Cuttapah & Ors AIR 1962 AP 260, (1961). “This result also flows from the following observations of the Privy Council in Ma Wun Di v. Ma Kin - “It is necessary before applying this presumption to make sure that we have got the conditions necessary for its existence. It is not superfluous to suggest that, first of all, there must be somebody of neighbours, many or few, or some sort of public, large or small, before repute can arise Again, the habit and repute, which alone is effective is habit and repute of that particular status which, in the country in question, is lawful marriage. The difference between English and Oriental customs about the relations of the sexes make such caution especially necessary. Among most English people, open cohabitation without marriage is so uncommon that the fact of cohabitation in many classes of society of itself sets up, as a matter of fact, a repute of marriage. But, in countries where customs are different, it is necessary to be more discriminating more especially owing to the laxity with which the word ‘wife’ is used by witnesses in regard to the connexions not reprobated by opinion, but not constituting marriage. […] On the evidence on record, there can be little doubt that the appellant belongs to the ‘Kalavathulla’ community and was treated prior to her becoming the mistress of Ramaswami as a devadasi. Exhibit B-11 establishes that she was one of the inamdars of the devadasi inam in Markapur. D.W. 2, he brother, admitted that their forefathers were entitled to devadasi inam in Markapur temple. The evidence on record and the surrounding circumstance clearly establish that the appellant was not lawfully married to Ramaswami but went to him as his concubine and lived with him in that status till his death. For these reasons, we uphold the Judgment under appeal and dismiss with costs;” Kumari Baghyavathi vs Smt. Lakshmikanthammal AIR 1993 MAD 346, (1992).

[16] Smt. Durgamma & Anr v. Shivashankara & Ors MFA No.8418 of 2007, (2011). “The confusion about the names of the father/husband is because of the pernicious practice of Devadasi system. It is a system, which has to be blamed for the present state of affairs;”